Russia’s history myths unmasked

Source: V. Putin: “Crimea Speech” (18 Mar. 2014) & “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” (12 July 2021)

Objective: Justification of Russia’s expansionist ambitions

TO ARTICLERussia’s war of aggression against Ukraine essentially put paid to any possibility for having positive connotations with the term “Russian World”. The concept of istoritcheskaya Rossiya (Eng. historical Russia) is still little known in the West, but its use by Putin and in the Kremlin’s propaganda has been on the rise for years, and its history as a concept stretches back much further.

Dekoder editor Dmitry Kartsev looks at the roots of these two concepts and explains why the ramifications of the second, “historical Russia”, may be even worse – in the region and in Europe – than those of Russkiy mir.

AI note: dekoder used Google Gemini to create this illustration

The term Russkiy mir (Eng. Russian World) first began to crop up in the speeches of Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev in the first decade of the 21st century. The concept had been developed earlier, although the Kremlin leaders first used it to support the idea that “Russians” who had fled abroad for political reasons during the Soviet era or shortly after the USSR’s collapse continued to have a spiritual and cultural bond with post-Soviet Russia.

That this concept has an expansionist

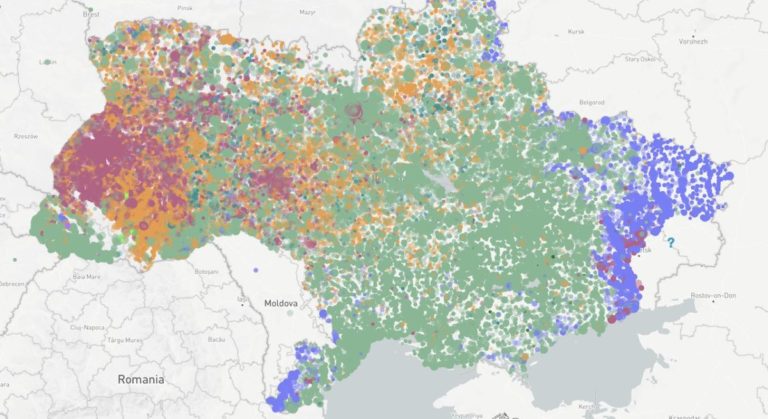

edge became apparent upon the annexation of Crimea in 2014. In the address known as his “Crimea Speech”, Putin implies that ethnic, in the sense of this “Russian world”, Russians have a right to live together in one and the same state. That state being Russia, naturally. Moreover, the term “Russians”, as understood by Putin and as used in his propaganda, encompasses Ukrainians and Belarusians.

Putin speaks of both russkiy mir and istoritcheskaya Rossiya in his “Crimea Speech”, using the two terms more or less synonymously. That address was not the first time Putin referred to “historical Russia”: he had already done so in one of the articles he wrote for the 2012 electoral campaign, announcing that Russia had been, was and would remain a multi-ethnic state, in which “hundreds of different nationalities [were] living in their territories together and alongside Russians.”

The concept of “historical Russia” first appeared in the writings of conservative Russian thinkers in the 19th century. Later, after the Russian Revolution in 1917, émigré philosophers – among them Ivan Ilyin, who is very much admired by Putin – contrasted the “historical Russia” with the Bolshevist regime.

In recent years, Putin has spoken more and more of “historical Russia”. A case in point is his infamous essay “On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians” of July 2021, which sets out his ideological justification for the full-scale war of aggression against Ukraine.

From a purely historical viewpoint, both terms are clearly very problematic: both suggest that the populations of all countries and territories that – according to Russian school textbooks (i.e. the state narrative of Russian history) – belonged to Russia at one time or another must link their histories with that of present-day Russia.

To suggest this is to ignore all other historical perspectives, as well as the fact that many of the regions in question were conquered militarily. This narrative relates not only to independent countries like Ukraine, Belarus and Latvia, but also to territories within Russia, whose past it reduces largely to their relationships with “Great Russia”. The implication is that this connection had almost exclusively positive aspects.

That this narrative finds an audience testifies to the fact that the work necessary to engender a full understand the history of Russian colonialism has yet to be done. History books speak of Russia’s “expansion” or its incorporation of new territories, seldom addressing subjects like the colonial rule over lands and societies which, to some extent, belong to Russia to this day.

Russia’s official narrative never mentions that the various states and proto-states that figure in it are often in competition with one another and with present-day Russia. For instance, those twentieth-century Russian émigré philosophers mentioned above, who made frequent use of the term “historical Russia”, viewed Soviet Russia not as a continuation of the Russian Empire but as a break with it. The assertion in the Kremlin’s propaganda that Russia’s roots lie in Ancient Rus is also a controversial one among historians.

Paradoxically, history actually plays only a very limited role in Putin’s interpretation of “historical Russia”: he is not interested in societal developments but rather in the geographic boundaries of the area that Moscow now sees as “Russia”.

The concept of the “Russian World”, for its part, gives a metaphoric home to the political idea that the “Russians” (here, referring primarily to Russian-speaking populations) living outside of Russia (especially those in countries adjacent to Russia) identify chiefly with Russia. This gives the Kremlin a “right”, if not a duty, to “protect” them. Examples of what this “protection” can look like on the ground have been playing out for the entire world to see in Ukraine for almost four years now.

Needless to say, neither concept is compatible with international law.

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has essentially put paid to any possibility of having positive connotations with the “Russian World”. The other concept, “historical Russia”, is less well known in the West, but in Putin’s interpretation, it may well be the more dangerous of the two.

Back in 2016, Putin announced that Russia’s borders did not end anywhere. Though intended as a joke, this sounded ominous even at the time, two years after the annexation of Crimea. In the summer of 2025, Putin told the International Economic Forum in St. Petersburg: “Wherever a Russian soldier sets foot, that is ours.”

While the “Russian World” concept is – albeit often only ostensibly – about cultural, societal, linguistic and spiritual ties, the concept of “historical Russia” explicitly conveys that conquest in the past is in itself sufficient to justify present-day territorial claims on the part of Moscow. Thus, war itself is legitimised as a policy tool.

Moreover, a look at the original meaning of the term as it was first used in the political commentary of Russian conservative thinkers of the 19th century can be enlightening: one of them explains that historical Russia is ideally a country with a strong governmental power, individual and vibrant, not collective and contingent. This language, too, should resonate with Putin, given his illiberal and autocratic form of government.

Whether Putin will expand Russia’s war into Europe is not clear at this time. But the ideological justification for an escalation of this kind has already been laid out.

We are publishing this piece in cooperation with the German section of the Deutsch-Russische Geschichtskommission (Joint Commission for Research into the Recent History of German-Russian Relations) and BKGE (Federal Institute for History and Culture of the Germans in Eastern Europe, Oldenburg).