Russia’s history myths unmasked

Do the myths a society tells itself about its history determine how it perceives itself? Or do certain patterns of thought have to develop first to enable such myths to spread?

At least since its annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia has been “positioning” the past for its own propagandistic purposes, misusing history as an aid-de-camp in its war of aggression against Ukraine and its confrontation with the West. But historical propaganda would not be taken up so well in Russian society if it were not able to build on patterns of thought that developed long ago.

This is why we have chosen to launch our new special – devoted to decoding the Kremlin’s historical narratives – with an exchange of letters between journalist Andrei Arkhangelsky and historian Sergei Medvedev, in which they explore the toxic and deadly thought patterns that lie behind Russia’s myths about the past.

AI note: dekoder used Google Gemini to create this illustration.

Andrei Arkhangelsky: I thought we could start with personal thought patterns, the kind we are not even aware of or only become aware of as we grow older. The ones that demand that we do some hard work on ourselves.

We were both born in what was still the Soviet era – in its complacent years under Brezhnev (also known as the era of stagnation). This was in the late 1960s, early 1970s. What were those first ideas I had about my country and the world? Foremost among them was that I was lucky to have been born in the best country in the world, the USSR: this was the self-evident basis for everything else. I can even describe the feeling on a scale of colours: “our country” has the place in the sun, in the bright light, with no cracks or gaps – and the light is produced by the country itself (like a perpetuum mobile).

Next come the other socialist countries. It’s light there, too, but with stripes, like the ones on their flags, white alternating with, let’s call it grey. And finally, the “countries of capital” and all the others – situated along a spectrum from violet to black. The darkness in the US, for instance, is impenetrable.

I also had the feeling that the Soviet Union could replace the whole world, that we didn’t need “the others” at all, because we were already a “whole world” in and for ourselves, “history in and for ourselves”.

The vast expanses of the Soviet Union contributed to this lucky-to-be-born-here thought pattern: “in the largest country, in the most immense of countries …” – we heard that from childhood on.

These are the central thought patterns; the others revolve around them.

How do you see this?

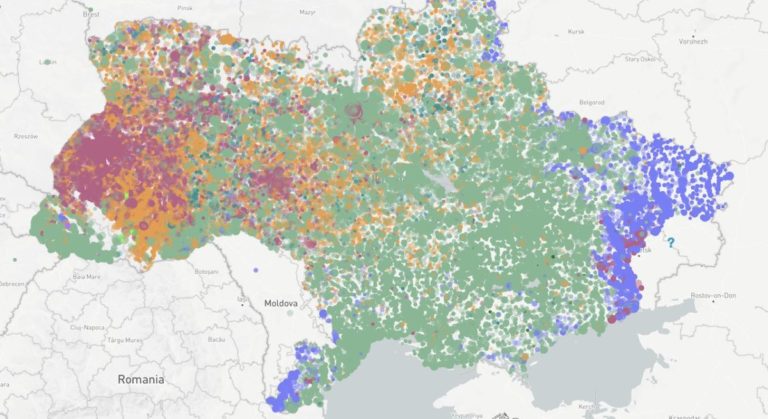

Sergei Medvedev: It’s very similar for me. I can still see myself, already a Young Pioneer, in my third or fourth year of school (1975/76): a winter morning, pitch dark outside, the rectangles of the windows of the house across the street gradually lighting up. I’m eating breakfast in the kitchen; I’m in my school uniform, its neckerchief pressed and carefully tied. Next to me, across the entire wall of the kitchen (for educational purposes, of course, but also to hide the peeling paint), is a political map of the world, its upper right corner proudly adorned with an area tinted a romantic pink and marked with the letters CCCP (USSR).

I read the names of the cities, from Kishinev [now Chișinău, Moldova – dek] to Uelen [near the Bering Strait in the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug – dek], and I’m filled with pride at the dimensions, the serene grandeur of this part of the world. My heart skips, and I think: What a stroke of luck for me, one little boy among billions of people on the planet, to have been born not just in this country, but actually in its capital city!

I even used to dream of a time when the pink patch on the map would grow even larger, when fraternal countries on our borders, like Mongolia, Bulgaria and Romania, would realize that it would be better to be part of this space – and we would become even bigger, even more wonderful.

It seems I’ve aged a bit since then, and I’ve reconsidered my views about that pink patch on the world map – but I have the sense that many of our compatriots never moved beyond that childish enthusiasm, that they still genuinely wonder why on earth all the other countries in the region don’t want to belong to us.

This myth about the greatness of the empire is one of the most persistent myths. People still stubbornly cling to the belief that Russia is somehow blessed: those nine time zones, the fabled Trans-Siberian Railway, the strategic depths, in which Charles XII [of Sweden – dek], Napoleon and Hitler all floundered in their day.

In fact, quite the opposite is true: the huge empire is a burden and Russia’s curse (incidentally, Ivan Ilyin, the religious philosopher so admired by Putin, wrote about this long ago).

These days, I give university lectures about this curse of vastness. The first time I flew to Chukotka [Autonomous Okrug, opposite Alaska – dek] from Moscow (as a student for a summer internship) I was staggered by the expanse of land we flew over, but not so much by pride at its size as by bewilderment at its senselessness. Holding such an expanse is like holding millions of square kilometres on Mars: it may sound great, but the reality is a pointless waste of resources in trying to develop those vast areas. Russia hasn’t managed that in 500 years.

Arkhangelsky: War and the Victory – that is the fundamental myth for my generation and for a few generations, before and after mine. The Victory was all-pervasive in my childhood. The Great Patriotic War, as World War II was known in the Soviet Union, (again, in a mythologised account thereof) allowed several robust narratives to take shape: “Russia is always the one that is attacked, it only defends itself”, “we never started any wars but we’ve always won them”, “we are the bravest and at the same time the most peace-loving”.

During perestroika, these narratives all seemed to be breaking down. For our generation (born in the late 1960s and the 1970s), the debunking came in a landslide: we had only just become familiar with all the “eternal topics” – the heroes of the Revolution, the 28 Panfilov heroes, the enthusiasm of the five-year plans – when they began to disintegrate under the hailstorm of new facts. In 1985, the weekly Ogonek, which I started reading at a young age (who didn’t?), began printing pieces about Stalinist repression, but also about the first months of the war and the “price of victory”. The start of the war was a veritable blank page in the official historiography; information had to be pieced together scrap by scrap.

The real history refuted the myth that “we didn’t have any military strength before the war”. But there were three thousand tanks in the Western Military District alone: a huge potential – the only thing lacking was the ability to use it. This revelation did not diminish the heroism of our grandparents’ generation, but it did cast doubt on the veracity of everything that had been imparted to us with so much pathos. This aroused an enormous interest in history – it would all essentially have to be learned all over again.

This new information did not have a profound impact on most Russians, though – we see that today. It baffles me, to be honest: that whole avalanche of new facts during perestroika – surely it must have flipped a switch in everyone, even the staunchest of the revanchists, Communists, etc.? Though actually, I now think that it did have an impact, that everyone did realise what it all meant. But then a defence mechanism kicked in across most of the population: “It just can’t all have been a lie, though, all be untrue, can it?”

Have you ever noticed the elegance with which post-Soviet society has, since the 1990s, dismissed anything that casts it in a negative or unpleasant light? Not with furious denials, but with post-irony: “boring and ridiculous”. I used to work for Ogonek, and by the 2000s I was hearing the publishers say things like: “Enough about Stalin, our readers are already bored by that. We need to look forward.” Then the Internet arrived and taught us to make jokes about everything… including repression. The typical, cynical post-irony online: “Sure, we were the ones who were always shooting, incarcerating and torturing everyone. It’s all Stalin’s fault.” As a method, it’s the perfect way for the vast majority to hide from the truth.

Exactly the same thing is happening today: any mention of guilt or responsibility for the war on the part of Russians is labelled “boring and ridiculous”, even in opposition circles.

Medvedev: With World War II, the situation is more complex. That isn’t just another Soviet state myth, it’s a foundational myth, the foundation of the Soviet identity. For all intents and purposes, the origin of our state (both our past and present-day state) goes back not to the frosty 7th of November (October Revolution Day), nor to the diffuse 12th of June (Russia Day, Russia’s national holiday) and certainly not to the fabricated 4th ofNovember (Unity Day, introduced in 2005), but to the 9th of May. Front and centre in this ontology is the expiatory sacrifice, death as salvation. This is what made it possible for the war mythology to replace Christianity as rapidly and easily as it did for many people. It helped, of course, that it falls in the spring – nature and the lilacs awakening to blossom, life victorious over death – a secular Soviet Easter.

As a child, I internalised this myth to a profound degree – not as Soviet celebration and ceremony but as a human story, one that two generations before me suffered through. There was no “cult of veterans” in our family. One of my grandfathers, a radio operator who made it all the way to Berlin, had long since left the family; the other spent the entire war in the gulag (17 years in total). But the 1970s, the decade I grew up in, were heavily influenced by the humanism of the Thaw. I used to draw poignant postcards – showing not tanks, but flowers and pinecones – and go watch the gatherings of veterans by the Bolshoi Theatre.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that this myth began to lose its humanity, to harden into stone, be buried by Breshnev’s Malaya Zemlja [Engl. Minor Land], and all those eternal flames. Then in the 1990s, the state took it over entirely, and in the 2000s it underwent a thorough transformation under Putin, becoming its opposite, the subject of a militaristic, chauvinistic carnival and state religion, complete with sombre temple and the devout processions of the Immortal Regiment.

The whole thing is repugnant, of course, but thinking back on my childhood, I understand how and why this myth works.

Bringing back our first myth, the myth of greatness: I think the propaganda combines these two elements quite cleverly – the myth of Russia’s greatness and the myth of the sacrifice marked by the 9th of May. The result is an explosive, mind-blowing mixture: the myth of the Victory as the chief paradigm of Russian history. Or in an even broader sense – the myth of war as the basic ontology of Russian life.

Russia is a belligerent country: it would be hard to find more than a few decades in the past ten centuries when Russia wasn’t at war with someone. You’ve got the military history, a war ethos and military elites, well into the 19th century – hence the cult of risk-taking, contempt for life, the love of duelling and card games, as [the literary scholar – dek] Juri Lotman pointed out with regard to the Russian nobility. And there’s the, the economy and consciousness; recruitment and conscription and the fatalism (“our grandfathers went to war, and we will too”). War is accepted in Russia in just the same way that the harsh winters or the hard-hearted regime are – you don’t talk about it, you survive it.

All of this was carried over seamlessly from the Empire to the USSR and from the USSR to the present day. And now, in the name of this myth, this narrative, Russia is waging another war – criminal, unnecessary, crude, but rendered sacred by tradition, inscribed in the myth and therefore natural and familiar to the populace.

Arkhangelsky: You expressed that marvellously – war as a substitute for religion. Incidentally, it is also war as an adventure (my grandmother, who lived through the entire war, would refer to a war film on television in the 1970s as “a wee film about the wee war”). All this glamourization of the war – turning it into a sport, as Anton Dolin once noted – had monstrous consequences. Among other things, it explains the emergence of the set phrase “We can do it again”. Only someone who has never been told the truth about war could ever speak of it in such a way.

The Shestidesiatnyky, the dissident generation of the 1960s, described of everyday life during the war truthfully, but even they didn’t write about the layers, the stacks of corpses that were the price paid for every patch of land taken. The daily conveyor belt of death, turning living human beings by their thousands into stiff rotting corpses was left out of the story. That’s what war is, though, for both sides. The German dead figured in the war literature, of course, but not our own. What an outrage that would have been! The Soviet dead are mentioned only in the personal reminiscences that happened to have been preserved. That’s where we find the “truth about war”, the truth that we now learn thanks to footage from drones and helmet-cameras…

In my opinion, the myth of “the war as religion” that you’ve described gives rise to two other important thought patterns. One is the myth that was drummed into us in Soviet times, and which is now being repeated: that the USSR defeated fascism all by itself (above all, without the United Kingdom and the US). And this accomplishment grants quasi an unlimited moral right to Russia and its population: “We defeated the evil in the world; therefore, the entire world will be forever in our debt; therefore, we are entitled to do anything. Mind you, this latter “we” is lacking in basic decency even with regard to the former “we”, which encompassed the populations of all former Soviet republics.

The second thought pattern deals with just what it is that this “we” considers to be “ours”: “Ours is everywhere that our blood has ever been spilled” (and we have fought almost everywhere). The poet Boris Slutsky wrote: “Our corpses lie buried in five neighbouring countries”. This squares with Putin’s “Russia ends nowhere”. The losses in the numerous wars over the course of several centuries – enormous, unnecessary and often, as history has shown, senseless – have become a bloody, symbolic capital for the Putin regime. The greater our losses, the greater the moral right to new conquests! Cynical, yes, but it works.

Moreover, this absolute entitlement, almost in passing, erases any sins from the historical memory: the 1939/40 attack on Finland, the 1940 annexation of the Baltic states, the “liberation campaigns” of the Red Army in Western Ukraine and Belarus and the annihilation of Poland as a state. It also erases the sin at the very root of all of that, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which amounted practically to unleashing World War II hand in hand with Hitler. These days (and in Soviet times), people tend to speak of this criminal pact as something Russia was “forced into, in order to gain time”. Even the publication of the secret additional protocols in the late 1980s could not shake this narrative: in the collective consciousness, this cooperation with evil is simply rendered unrecognisable, disguised as a “ruse of war”, a “trick”.

Medvedev: We now have a new definition of Russia’s borders: “Where the foot of a Russian soldier steps, that is ours”, said Putin in June of 2025. A boastful, pompous and entirely false assertion (what else should one expect from a professional liar): the feet of Russian soldiers tromped through Mukden and Port Arthur, through Afghanistan and Manchuria, and across the Alps with Suvorov on his senseless and foolhardy campaign, and from all those places, Russia withdrew in disgrace … Glorifying war, territorial expansion, the shedding of blood: this is an archaic activity. The argumentum ab sanguinis, invoking “the blood of the Russian soldier” and “the blood of our grandfathers” is the first sign of fascism, a biological definition of the nation as a collective body, as “blood and soil”.

It also explains the complete lack of historical reflection, the failure to look at our own history through a critical lens, and the inability to recognise the crimes of the past. Russian historical memory is carefully groomed, selective and superficial – it is mythologised and subordinated to the grand state narratives (victory, greatness, sacrifice in the name of a greater goal). At the same time, it is also hemmed in by repression and censorship, which steers a careful course around all sharp edges, such as questions of crime, responsibility, guilt.

The genocide of minority ethnic peoples [the “small nations”] during the expansion of the Russian Empire, the Stalinist deportations, Katyn, the war crimes of the Red Army in Europe in 1945 and of the Soviet army in Afghanistan, the extermination of Chechens that has been going on for 200 years – these are issues that are not registered by the mass consciousness, they are thoroughly tabooed, thrust into the “ghetto” of human rights defenders (e.g. into the publications and events of Memorial ) and branded anti-Russian by the authorities. We are left with a hollowed-out, one-sided and absolutely infantile image of history that conveys a false sense of greatness and an immutable historical “rightness”. A view that rules out any responsibility for the past and serves as a guarantee for new crimes committed by Russia in the name of its own history.

Arkhangelsky There is the silencing of inconvenient truths and the elimination of witnesses, and at the same time there is this emphasis of Russia’s special status as the alleged saviour of the world. This “eternal synthesis” gives rise to another thought pattern: put colloquially, “We’re all one people”. This pattern grew out of the history of colonial conquest, of course. Russian imperialism differs from the typical European “maritime imperialism”. European colonialism was based on the idea that there was a fundamental difference between the coloniser and the colonised, with the divide between the two considered insurmountable. The idea that underlies Russian imperialism is quite the opposite, at least as far as Ukrainians and Belarusians are concerned: the idea of sameness. “You are just like us, we are all one people,” says the coloniser, opening his arms disingenuously.

This creates an “elevator effect” [similar to that described by the sociologist Ulrich Beck in his 1986 book Risikogesellschaft on the influence of the “explosion of prosperity” on West German society after World War II – dek], opening new paths to success (when the next purge comes, you won’t be put up against a wall in your home region but in Moscow, the capital!). All you have to do is renounce your own identity in favour of a Greater Russian identity, and you, too, will get to make decisions about all the other “little nations” and lord it over the slaves of the empire. Under this Greater Russia theory, the empire also acquires a “right” to neighbouring territories, the so-called “historical lands”. Hence the concept of the Russkiy Mir interweaves with that of a “historical Russia” – the one that exists wherever a Russian soldier has once set foot.

In Putin’s ideology, Russia is a “victor nation”. Naturally, all the other peoples living in its vicinity secretly desire nothing more than to join this “victorious people”. A refusal to do so – as manifest in Ukraine’s fierce resistance – is met with genuine astonishment: Why not? What other version of greatness could there possibly be?

Due to their imperialistic consciousness, it does not even occur to them – and again, this obliviousness is genuine – that another people might consider this “greatness” to be completely irrelevant. They simply want to tend their garden and be left in peace.

So, from your perspective as a historian, is this myth of “one single people” a uniquely Russian instrument, granting the empire a right to colonise ad infinitum?

Medvedev: Uniquely Russian? No, of course not, and the first parallel that springs to mind is the myth of a united German nation, the geopolitical consequences of which shook Europe for a hundred years – from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. The formation of the German nation cost the world three big wars and millions of victims. And now, Russia, which got delayed along its path to modernity, is, broadly speaking, on the same historical trajectory that the Germans followed. And it is experiencing the geopolitical consequences of the romantic notion of the nation as a community of blood, language and destiny. Putin’s spiritual father in this respect is Solzhenitsyn, whose later political pamphlets laid out the basis for the notion of a single people made up of Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians, including Russian speaking residents of North Kazakhstan as well. This idea has become firmly entrenched in post-imperial minds.

The myth of the “one single people” as an organic entity of “blood and soil” takes us back to the biopolitical territory of fascism, which defines the nation in biological terms (even language becomes a biological, organic, corporeal phenomenon). “The Russian speakers”, “compatriots”, “Russkiy Mir”: these concepts are essentially fascist, and it is no accident that they underpin the discourse justifying the war in Ukraine and the destruction of Ukrainian statehood and identity. The same discourse could easily apply to aggression against Kazakhstan, Latvia or Estonia.

Arkhangelsky: The imperial consciousness accepts, albeit with a heavy heart, that the Baltic states and the former Warsaw Pact countries are now “foreign” for us. You’d have to look hard to find anyone in Russia these days who knows that Ukraine first proclaimed its independence in 1918, though, and an independent Ukraine has long been a torment to the imperialist consciousness.

The Soviet leadership was all too familiar with armed Ukrainian underground’s ferocious resistance to occupation in the western part of the country during the 1940s and 1950s. The Soviet central government sent in one NKVD secret-police division after the next to deal with them, and the secret reports from the time show that the local population was “almost entirely on the side of the insurgents”. Might this explain the great care that propagandists in the late Soviet period took in weighing how much content depicting Ukrainians as a people with agency they should inject to mass culture, into television programming? It could only ever be a folkloric kind of agency: “They are the ones who dance and sing so prettily.” Any Ukrainian writer, any artist who tried to raise the issue of national identity was immediately inundated with charges of “bourgeois nationalism”.

The present-day propaganda manages to out-ham even the ham-handedness of the Soviet output: today’s propaganda is premised on the negation of any kind of existence in its own right on the part of Ukraine (there is a historical parallel here: the same vehemence was evident in the denial of Poland’s having any kind of autonomous existence throughout the entire 19th century and again in 1939, a point on which, incidentally, the Nazis and the Communists were in marvellous accord). But how stupid does one have to be to tell Ukraine’s 52-million strong population to their faces, “you’re just a fiction”, “you don’t really exist” – and still hope to achieve an “ideological” victory over them?

The views even of pro-Ukrainian Russians are not free of repercussions from having the idea of Ukraine’s “lack of standing as a sovereign state” drummed into them for decades. This can be heard in the rhetoric of opposition activists at demonstrations in Berlin: particularly at the first protest, it was palpably apparent that the speakers simply had no language with which to talk about Ukraine.

Medvedev: In fact, completely the opposite situation applies: Ukraine’s statehood is fully developed. Indeed, it grows stronger with each day of the war, whereas Russia is gradually forfeiting its own status in this respect. In the course of this war, Ukraine completed the process of forging itself into a political nation, tempering that nationhood in the fire of battle. In addition to having the most combat effective army in Europe, Ukraine has become a significant player on the international stage, engaging with the great powers on an equal footing.

Russia, though, does not enjoy the standing of a fully developed state along either the internal or the external dimension of that concept. Internally, it has ceased to be an empire but has yet to become either an ethnic or a civic nation. Russians have not become a true polity: they remain just a population, a statistical aggregation. Russia does not enjoy the full standing of a sovereign state externally either, with its illegitimate and unrecognised borders and its president being the subject of an international arrest warrant.

I think this whole Russian narrative about Ukraine “lacking statehood” is rooted in envy, in this very lack of independence, identity and dignity on the part of Russia itself. Brzeziński described Ukraine as being a cornerstone of the empire and said the Russian empire would lose its meaning without Ukraine. The loss of Ukraine became a fundamental trauma for the Russian imperial consciousness. This trauma is at the core of Brodsky’s vituperative On the independence of Ukraine, a poem that devastated his fans and does not fit easily into the canon of the rebellious Nobel laureate poet. The poem is actually an enraged shriek from the Russian imperial consciousness, whose competent representative Brodsky felt himself to be. As did Pushkin, incidentally, another imperialist poet.

Russian resentment of Ukraine is a blend of two feelings: the aggrieved indignation of a gentleman deprived something that had seemed to be rightfully his (Ukraine was seen as especially close to Russia, so close that there was hardly any difference between the two, which is why its departure was taken as such a painful betrayal) and a slave’s impotent envy of someone who is free.

The best medicine against all these myths – of greatness, victory and the right to unlimited expansion, of Russia’s uniqueness and the inferiority of the peripheral parts of the empire – would be a defeat of Russia in Ukraine, like the one Germany experienced in 1945. I fear, though, that even that would not help the dying power, immersed in hallucinations of its former greatness.

Arkhangelsky: “Hallucination”: that describes it very well. The myth of boundless greatness is a substitute for the empire that was lost. And the more obvious the loss becomes, the more powerful the mass hallucinations grow. This threadbare myth of greatness is coupled with two patterns of thought. One – and this one has been around for centuries (practically since the world was created) – is that “everybody envies us and wants to conquer us to get our riches”. The recent Russian pop hit Matushkazemlya sums up these clichés in the simplest form: “Mother earth, white birch, for me Holy Rus, for others a thorn in the eye.”

The whole world dreamt of subjugating and conquering us: this is also part of what lies behind Putin’s assertion about the “expansion of NATO right up to the borders of Russia”, which was one of the formal reasons cited for the unprovoked aggression against Ukraine. This universal egocentrism means that any and all actions are only ever seen as being “for” or “against” Russia.

I would like to finish up by looking at a thesis that Putin’s propagandists have been at pains to inculcate in the populace: “All revolutions in Russia were started by external forces”. Not even the Revolution of 1917 is spared in this respect: there’s a version of history being propagated these days that describes it as an “operation of the German General Staff”. One is left literally speechless. In just a quarter of a century, the fundamental pillar of Soviet ideology has been completely forgotten: the USSR, the world’s first workers’ and peasants’ state, born of the October Revolution. Propagandists were the ones who, in line with the ideological dogma, understood the Revolution as the loftiest of human achievements, as the authentic creation of the masses themselves, and as having sparked the “revolutionary fire” throughout the world. This, as recently as in the 1970s. And now, they are out there, with wild eyes and a brutish look on their faces, labelling other countries’ revolutions “coups d’etat” (above all the 2014 Euromaidan in Ukraine).

Do they actually believe the things they are saying? That was a rhetorical question, of course. This kind of duplicity – even when it comes to their own history – tells us a lot about those who practise it: above all, that nothing is sacred to them and they have no respect for the past.

Medvedev: In deconstructing the myths and typical thought patterns we’ve been discussing, I’ve come to realise that they are all the deliberately constructed product of centuries of work by state-controlled propaganda machines, cultural elites and academic training and school education. They seem to be eternal, and they are now being reproduced by the mass consciousness. The truth is, though, that these ideas are the product of intentional mythmaking that has served the interests of the state and the empire in multiple historical periods: from the Muscovite and Imperial periods on through to the Soviet and post-Soviet periods.

Thus, all these myths are extremely toxic because they keep the mass consciousness locked into a paradigm of imperial thinking, in myths about the greatness and uniqueness of Russia, its culture and its civilization, about the eternal war with the West and the eschatology of victory. There were attempts in the 1980s and 1990s to examine these myths through a critical lens, but these efforts failed to result in long-term, institutional change and are now branded as a “betrayal”.

In the name of these myths, a war of aggression is being waged against Ukraine today, peaceful cities are being bombarded. At the same time, the war is being normalised and the mass consciousness is being soothed in Russia itself. In this sense, the romantic dreams of Russian empire are not only toxic, but de facto deadly.

We are publishing this piece in cooperation with the German section of the Deutsch-Russische Geschichtskommission (Joint Commission for Research into the Recent History of German-Russian Relations) and BKGE (Federal Institute for History and Culture of the Germans in Eastern Europe, Oldenburg).