Russia’s history myths unmasked

Source

V. Putin: „On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians“ (12 July 2021)

Objective

Legitimation of Russia’s sphere of influence

Long-term: Invasion of Ukraine

Moscow describes “Ancient Rus” as the cradle of the “Russian people”, the origin of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation of the present day. In doing so, it is using well over a millennium’s worth of history – history that played out substantially to the west of Moscow, on the territory of today’s Ukraine and Belarus – to construct a narrative aimed at justifying the use of hybrid measures to influence other states and even a destructive war against neighbouring states.

A particularly clear case in point is Vladimir Putin’s article “On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, which was published on 12 June 2021, about seven months before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Two years later, Putin told this story once again, this time to the World Russian People’s Council.

The myth is problematic in many respects: however it is told, Russia’s narrative completely disregards both the facts and the diverse development – often independent of Moscow – of Rus populations in other historical perspectives. And anyway, why Russia? Why should a (false) narrative about a common historical origin of Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians entitle the Russian state in particular to dominate its neighbours and even use violence to enforce that dominance?

Historian Andrey Doronin takes a deep dive into the historical underpinnings of the Russian myth that Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians are “one people – a single whole” and explains how the understandings of the non-Russian Rus differ from the myth that Moscow tells.

AI note: dekoder used Google Gemini to create this illustration.

In the modern paradigm, a people traces its history back, not to the emergence of its statehood, but to its emergence as a nation. Thus, in this understanding, a nation is older than its institutions of government because the latter grow up out of the nation. And the actual state, as an entity, takes shape only at a later stage of national self-organisation; it is the nation that comes first.

In the modern era, the nation grew stronger than the individual institutions of government, the Church, the social estates, etc., displacing them within a hierarchy of social institutions and subordinating them to itself.

Every modern European nation, as well as the institution of the modern nation per se, begins with an origin myth of this kind, one which tells of the antiquity and distinctiveness of its ethnocultural “ours-ness” [“nash”, ours, here that which makes us us – dek]. But this nation paradigm is too narrow for Russia, which has its own dimension of history. For Russia, the dominant component in the hierarchy of identities is not the individual or civil society, not the nation or the project of a common transnational Europe: it is the state.

For Putin’s Russia, the state is the beginning and the foundation, the backbone and guarantor, the symbol of the Russkiy Mir, which it inherited from the early Rurikids and which has, supposedly, existed for all those centuries with no discontinuity at all. In Russia’s telling, the centuries of cultural divergence within the rus1 and the multi-vectoral nature of its history are presented as centuries of subjugation of the rus by other peoples and of aspiring to free itself of this “yoke”.

In addition to serving as the starting point for the Russian state’s narrative of its history, the Rus of the 9th to the 13th century is a part (but not the beginning!) of the national history of the Ukrainians and the Belarusians. It also figures in regionally specific narratives of Rusyns in Slovakia, Poland, Hungary and Romania. The rus of that time is woven into multiple narratives of history and is depicted differently in each of them. The non-Russian (state) rus creates an ethnocultural construct of its origins and of a different rus-ness; the Muscovite rus creates a state-centric, imperialist Rus(s)-ness.

Why, though should any rus – after existing independently of the Muscovite rus for a long time or even for its entire history – be obliged to fall in line with a narrative of rus-ness or rather, Russianness for which Moscow claims monopoly rights?

In rus national or regional narratives, the rus (the peoples, the ethnic groups, the subethnic groups) often do not associate their beginnings with the Rus of the 9th–13th century or with statehood.

Russia is making assertions about its origins and a continuity of power. In the earliest chronicles, written from the perspective of the ruling Rurik dynasty, Kyivan Rus is presented as a conglomerate of principalities which is politically and religiously united and whose population is heterogeneous, both ethnoculturally and linguistically. The Kyivan throne passed from one member of the ruling dynasty to the next according to rules of agnatic seniority rather than inheritance.

There were times in which the Kyivan throne was held by princes from multiple Rurik houses within a single year. The ruling dynasty grew and with it, the number of its branches. Rather than wait for a turn on the throne that was unlikely to come, appanage princes tended to fortify their own holdings for themselves and their descendants. Regionalisation within Rus grew ever more pronounced, and by the start of the 13th century one could no longer speak of a transregional commonality of Rus’ lands.

To Kyiv itself and the free cities of Novgorod und Pskov were added the principalities of Polatsk, Smolensk, Vladimir-Suzdal, Ryazan, Chernigov, Pereyaslavl and Galicia-Volhynia. Becoming practically independent, these principalities continued to be divided up further and they continued feuding as well. What united them all was primarily the common dynasty and the Orthodox religion. What divided them was land: to each (princely house) its own.

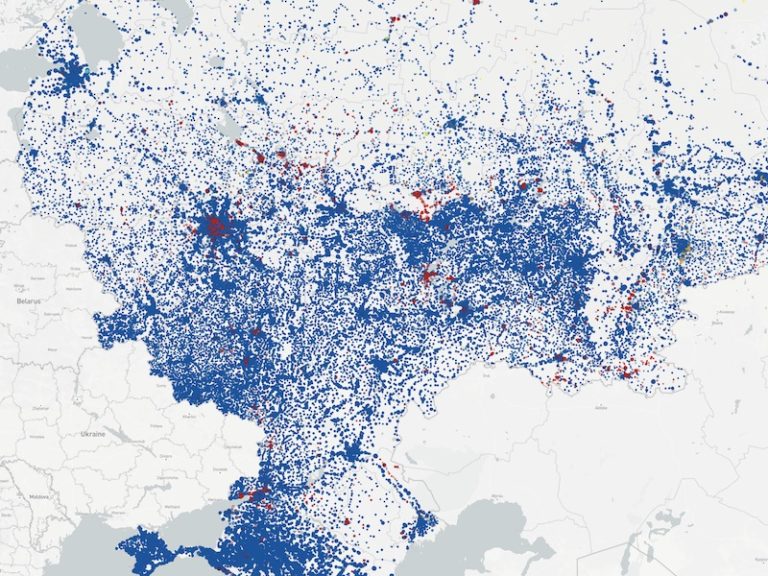

The Mongol invasion of 1237–1240 led to the disintegration of the ruling house of the Kyivan Rus. Some formerly Rus lands were integrated into other state entities: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland – and after their union in 1569, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Other formerly Rus territories came under the rule of the Golden Horde.

The principality of Galicia-Volhynia remained independent until the 1320s; the principality of Kyiv and Novgorod both held on to their independence until the 1470s. By the end of the 15th century though, the rus was basically divided into a Lithuanian rus and a Muscovite rus; the division of the Metropolis of Kiev weakened cross-border ties even further.

Those of the Rus lands that were incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania or the Kingdom of Poland (rather than becoming provinces of the Golden Horde) now found themselves within the sphere of influence of the Holy Roman Empire. They began to adapt, to a greater or lesser degree, to some aspects of Western culture.

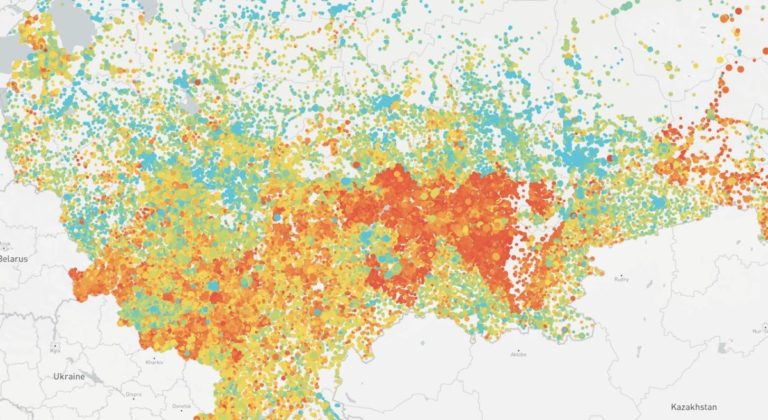

In the early modern era, various rus-groups began to reshape themselves as ethnocultural “we-groups” in new political and cultural spaces, each adopting aspects of the (early) modern pan-European coordinate system in its own fashion. Each of these groups sought to find a new place for itself on the political and cultural map of Europe – whether on a basis of independence or of inclusion. This process, shaped by the co-existence, confrontation and interaction between the various historical and cultural lines of self-identification, played out against the backdrop of the intensifying church polemics, which came to a peak in the 17th century.

Russia did not claim to be the successor of the early Rurikid rulers until the latter half of the 17th century.

At this time, the entire diverse rus did not necessarily see itself as originating in the Rus of the 9th–13th century. There was no uniformity in the rus’ ideas about its beginnings, not even across members of the same social or political class or church.

Even Russia did not claim to be the successor of the early Rurikid rulers until the latter half of the 17th century, instead seeing its history as a principality as rooted in the 13th century. Kyiv, a shadow of its former self, had long since belonged to another state. Moscow invoked Holy Prince Vladimir, the Baptist of Rus, only in prayers. Until the 1630s and 1640s, that is, when the idea of a continuity between Russian statehood and the early Rurikid rulers began to be pushed by clerics from Kyiv, who would travel to Moscow to solicit support for their Orthodox church.

By the 17th century though, other rus-Ukrainian intellectuals were generally of the opinion that the rus and the moskva were not the same people. This was the opinion, for instance, of the author of the Hustynja Chronicle (1620s), who conscientiously collected all the accounts of the origin of the Slavs known at the time (primarily, though not solely, from classical sources). The chronicler also points out that Pryazovia [area around the Sea of Azov, the Ukrainian part of which lay outside of Rus‘ territory – dek] (from whence, he believed, the rus and the moskva once came) had, since the time of the Trojan War, also been inhabited by another Slavic-speaking people: the Circassians (Cossacks). A few decades later, Cossack chroniclers took this reference, in conjunction with 16th century Western works that placed Khazaria in the same area, as a reason to present the Cossacks as descendants of the Khazars, and hence supposedly the original inhabitants of “Malorussia” (Little Russia).

The “Khazar myth” became the foundation for the new historical identification of the population of “Malorussia”. The potential of this myth for the consolidation of Ukraine did not fade over the entire period that Ukraine formed part of the Russian empire. The Rus of the 9th–13th century played only a marginal role in this myth, as a later stage of the national history.

In the 19th century, the Khazar myth became the basis for an updated version of Ukrainian nationalism. In 1862, Pavlo Chubynskyj penned the famous verse, which became the core of the Ukrainian national anthem:

We will lay down body and soul / for our freedom / and we will show that we, brothers, are of the Cossack nation.

The rus of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania did not create a national narrative of its own in the early modern period, but instead let its origins meld with the Litvin narrative: as early as in the latter half of the 16th century, the rus there saw its origins exclusively in connection with the origins of the litva.

Moreover, the grand duchy was unusual in the degree of tolerance within its society: the rus and the litva adapted their ways to accommodate one another at various social levels of everyday life.

The territory inhabited by the rus within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had no administrative autonomy of any kind, but the language spoken by the rus remained an official language (initially the primary official language) for a long time. Generally, the rus’ familial, local and regional ties in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania of the 17th century were stronger than its transborder, ethnocultural ties. In the 19th century, the early proponents of Belarusian nationalism called for “eternal unity” with Lithuania, where, as they saw it, the rus was like the “kernel in a nut. They did not view their history as starting in the Rus of the 9th –13th century.

A substantial portion of the rus stopped seeing its origins as rooted in Kyivan Rus and viewing its past as associated with the Muscovite principality

Regional identification remained central to the rus from the collapse of Rus until the 17th century, when independent nations began to develop in Eastern Europe. A substantial portion of the rus did not associate its past with Moscow and did not recognise the Muscovite Rurikids as the rightful heirs of the Rus of the 9th–13th century. Even after being integrated into the Russian Empire, the rus there continued to draw a distinction between itself and the Muscovite rus.

The notion of a united Russian people/ Russki Mir that has existed since ancient times is manifest only in two narratives: the imperialistic narrative (the rus = subjects of the Russian state) and the religious narrative (the rus = Russian Orthodox). Yet the rus/Rus was historically and remains plural.

Accordingly, we must speak in terms of different historical narratives of ours-ness, of different historical perspectives and different ethnocultural groups, nationalities and peoples.

We are publishing this piece in cooperation with the German section of the Deutsch-Russische Geschichtskommission (Joint Commission for Research into the Recent History of German-Russian Relations) and BKGE (Federal Institute for History and Culture of the Germans in Eastern Europe, Oldenburg).

Author’s note

Why isn’t the word rus capitalized here?

There are a variety of “we-groups” that can be traced back to Rus. I understand rus to refer to those we-groups that associate their pasts and institutions with Rus after its collapse in the 13th century.

The term rus is not an ethnonym. It began to gain currency in the 14th century in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and later in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where it was used to refer to people living in the territories of what had been Rus. The litva and the Polish called them Ruthenians or Rusyns to distinguish them from themselves. In those days, it was still the norm in northeastern Europe for people to call themselves by names based on the specific region they inhabited: the Suzdalians, the Novgorodins, the moskva and so on.

The use of the collective term rus enables me to avoid using the term “russkiy” [which used to mean only ethnic[ally] Russian], the use of which as a synonym for “rossiyskiy (of the Russian state) is being promoted these days.

Translator’s note

“Rus” is generally capitalised in Russian contexts, as it normally refers to the medieval “conglomerate of principalities”. As explained in the author’s note on the term above, in its uncapitalised form, “rus” refers here to groups of people (defined above) and allows the author to avoid using the modern-day nouns derived from adjectives denoting an association with Rus (e.g. Rus(s)ian). Russian orthography does not call for the capitalisation of demonyms, ethnonyms etc. (a male ethnic Russian is russkiy, for instance). The author uses uncapitalised forms of two other toponyms analogously (at least to some extent): “litva” refers to a Lithuanian population group that differentiates itself from the rus, “moskva”, presumably, refers to a population group that associates itself with Moscow. The uncapitalised form of these three words is retained here to avoid weakening the visual impact of the author’s idiosyncratic usage. Rus is writ large (figuratively speaking) quite often these days. Neither this, nor the substantial linguistic awkwardness caused by use of a singular collective noun to refer to any or all of a set of diverse groups of people will have escaped the author’s notice.